Judge Patrick Smith of the Specific Claims Tribunal has issued a ruling in favour of the Popkum First Nation (“Popkum”) with respect to its claim regarding the Seabird Island Reserve. Judge Smith found that in divesting Popkum of its interest in the Seabird Island Reserve without compensation and distributing part of its share of the Seabird Island trust monies to a newly created Band (a non-beneficiary at that point in time), Canada breached its duties to protect Popkum’s interests from exploitation. The decision, which is another victory for a First Nation claimant at the Specific Claims Tribunal, upholds a high fiduciary standard on Canada when seeking to divest a Band of Indian Act reserve land and monies.

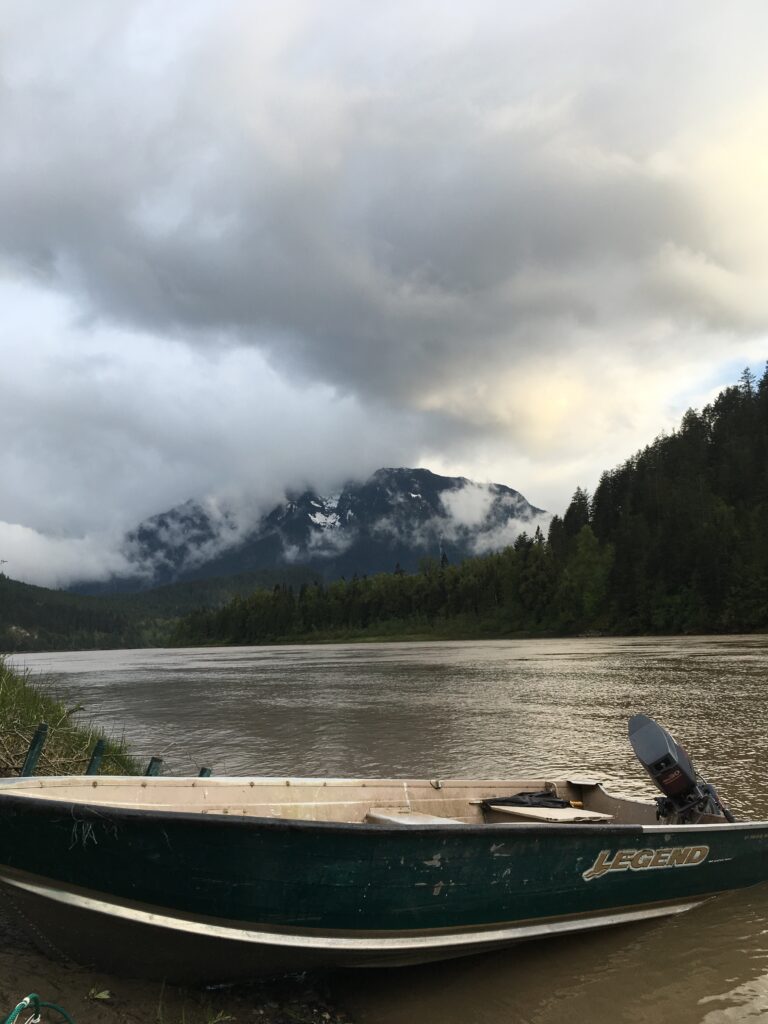

Photo credit: Gordon Lyall

FACTS

In 1879, Indian Reserve Commissioner Sproat (“Sproat”) set aside the Seabird Island Reserve (“Reserve”) for seven Bands in common (including Popkum) to provide them with sufficient cultivable lands to sustain themselves. The Tribunal briefly reviewed Sproat’s mandate and authority including the history of the Province granting Sproat final authority in the District of Yale; the Tribunal also briefly reviewed the statutory origins of the Railway Belt in which the reserve was located. The Popkum First Nation alleged that the Reserve was confirmed in 1879 or 1883 at the latest, however the Tribunal declined to make a finding on this point because the record relating to reserve confirmation was incomplete and because a finding as to the exact date of confirmation was not necessary to resolve the claim.

In the decades that followed the allotment of the Reserve by Sproat, the residents of the Reserve petitioned the Department of Indian Affairs (“DIA”) to become a separate Band. In 1918, DIA began keeping an unofficial Seabird Island Band list and trust account and the residents considered themselves a separate Band. However, officially the Reserve and the Seabird Island capital and revenue accounts continued to belong to the seven Bands.

Because the Reserve was allotted to seven Bands in common it became difficult administratively for Canada to get the required consent for developments on the Reserve (such as the granting of rights of way). In order to address this problem, the DIA approached the seven Bands in the 1950s regarding their willingness to relinquish the Reserve and its associated trust fund. The Popkum Chief, as the sole member of the Band Council, issued a Band Council Resolution (“BCR”) in 1951, releasing Popkum’s interests in the Reserve in favour of the Seabird Island Band.

In 1959, the Minister pursuant to s. 17 of the Indian Act established the Seabird Island Band and allotted the Reserve to the new Band. The Minister also distributed the funds in the Seabird Island capital and revenue accounts on a per capita basis among the members of the seven Bands and the new Seabird Island Band. There was no evidence that any members of Popkum resided on the Reserve at the time the Minister made her decision.

Photo credit: Gordon Lyall

LEGAL ANALYSIS

Canada argued that the Minister exercised her discretion pursuant to s. 17(2) of the Indian Act which states:

Where… a new band has been established from an existing band or any part thereof, such portion of the reserve lands and funds of the existing band as the Governor in Council determines shall be held for the use and benefit of the new band.

Canada argued that s. 17(2) did not require the consent of Popkum but that even if it did, consent was obtained through the 1951 BCR.

Canada also argued that by the time of the decision to establish the Seabird Island Band, the residents of the Seabird Island Reserve had gained an equitable interest in the Reserve and thus while Canada had a fiduciary duty towards Popkum, the duty did not require Canada to protect the interest of Popkum above those of the new Band. Canada argued that if it had to protect Popkum’s interests above the interests of the new Band, this would render the discretion granted by section 17(2) impossible to exercise. Rather, Canada argued that its fiduciary duty should be limited to avoiding unconscionable acts. The Tribunal disagreed with Canada’s position.

Judge Smith determined that, except as members of one of the seven Bands, the Seabird Island Reserve residents (who would go on to become members of the Seabird Island Band), did not share an interest in the Reserve either individually or as a group prior to the official creation of the new Band. Judge Smith found that the Indian Act prohibited the acquisition by third parties (in this case, the residents of the Reserve) of interests in reserve land by occupation or various forms of acquiescence or agreement and that this was consistent with the purpose of the Act – to protect a Band’s reserve interests from erosion and to ensure a Band’s interests in land are only alienable to the Crown. Thus, a resident of the Reserve or the Seabird Island Band could not have obtained an interest in the Reserve simply as the result of use and occupation.

Moreover, the situation was distinguishable from Wewaykum Indian Band v. Canada, 2003 SCC 45 (“Wewaykum”), where it was found that two Bands had an equitable interest in each other’s reserves. Wewaykum involved a dispute between recognized Bands regarding provisional reserves (that were not yet formally protected by the Indian Act), each Band acquiesced to the other Band’s presence, and an error had been made in the Schedule of Reserves. However in this case, the Reserve was an Indian Act reserve and the Seabird Island Band did not officially exist until its recognition in 1959. Thus the Seabird Island Band had not acquired an equitable interest in the Reserve prior to 1959.

Judge Smith also found that s. 17 of the Indian Act did not contain clear language removing or modifying established fiduciary obligations and thus Canada still had fiduciary duties towards Popkum that included the duty to preserve and protect Popkum’s interest in the Reserve against exploitation. Moreover s. 17(2) could only be relied on when reallocating the assets of an existing Band when the new Band at least in part was composed of members of the old Band. In this case, there was no evidence before the Minister that any of residents of the Reserve were Popkum members. As a result Judge Smith concluded that:

The Minister’s reallocation of Popkum’s one-seventh interest in the SI Reserve to the SI Band was a reallocation from a confirmed reserve holder, Popkum, to a non-beneficiary [the Seabird Island Band] of Popkum’s interest. The discretion afforded by section 17(2) does not extend this far.

Judge Smith found that the 1951 BCR did not absolve Canada of its fiduciary responsibilities because the transaction was improvident: Popkum had no legal representation and was not fully informed of what it was entitled to and what it was consenting to. Thus, Judge Smith concluded that Canada breached its fiduciary duty in divesting Popkum of its interest in the Reserve. In particular, he stated:

With the Minister’s action pursuant to section 17, the Crown relieved itself of administrative complexity in the exercise of its fiduciary and statutory duties at the expense of Popkum’s legal and equitable interest in the SI Reserve. The actions of the Crown were self-serving, relieving itself of an administrative headache at the expense of Popkum.

Judge Smith also found that Canada had no authority to distribute Popkum’s interest in the trust funds pursuant to section 17 and therefore it required the consent of Popkum before it could do so. The funds should not have been distributed to the members of the Bands and the Seabird Island Band on a per capita basis. Canada ought to have distributed the funds on a per Band basis instead and since the Seabird Island Band had no interest in the funds it should not have received a share.

With this decision the Tribunal does not add to the law regarding Canada’s obligations in the reserve creation period (as with Kitselas and Williams Lake) but does reinforce the fiduciary duties binding on Canada when making decisions under the Indian Act.

This case summary provides our general comments on the case discussed and should not be relied on as legal advice. If you have any questions about this case or any similar issue, please contact any of our lawyers.

See CanLII for the Reasons for Judgement.