In a watershed decision released today, the Supreme Court of Canada (“SCC”) allowed the Tsilhqot’in Nation’s appeal and, for the first time in Canadian history, granted a declaration of Aboriginal title. In doing so, the Court confirmed that the doctrine of terra nullius (that no one owned the land prior to Europeans asserting sovereignty) has never applied to Canada, affirmed the territorial nature of Aboriginal title, and rejected the legal test advanced by Canada and the provinces based on “small spots” or site-specific occupation. The SCC overturned the Court of Appeal’s prior ruling that proof of Aboriginal title requires intensive use of definite tracts of land and it also granted a declaration that British Columbia breached its duty to consult the Tsilhqot’in with regard to its forestry authorizations. This case significantly alters the legal landscape in Canada relating to land and resource entitlements and their governance.

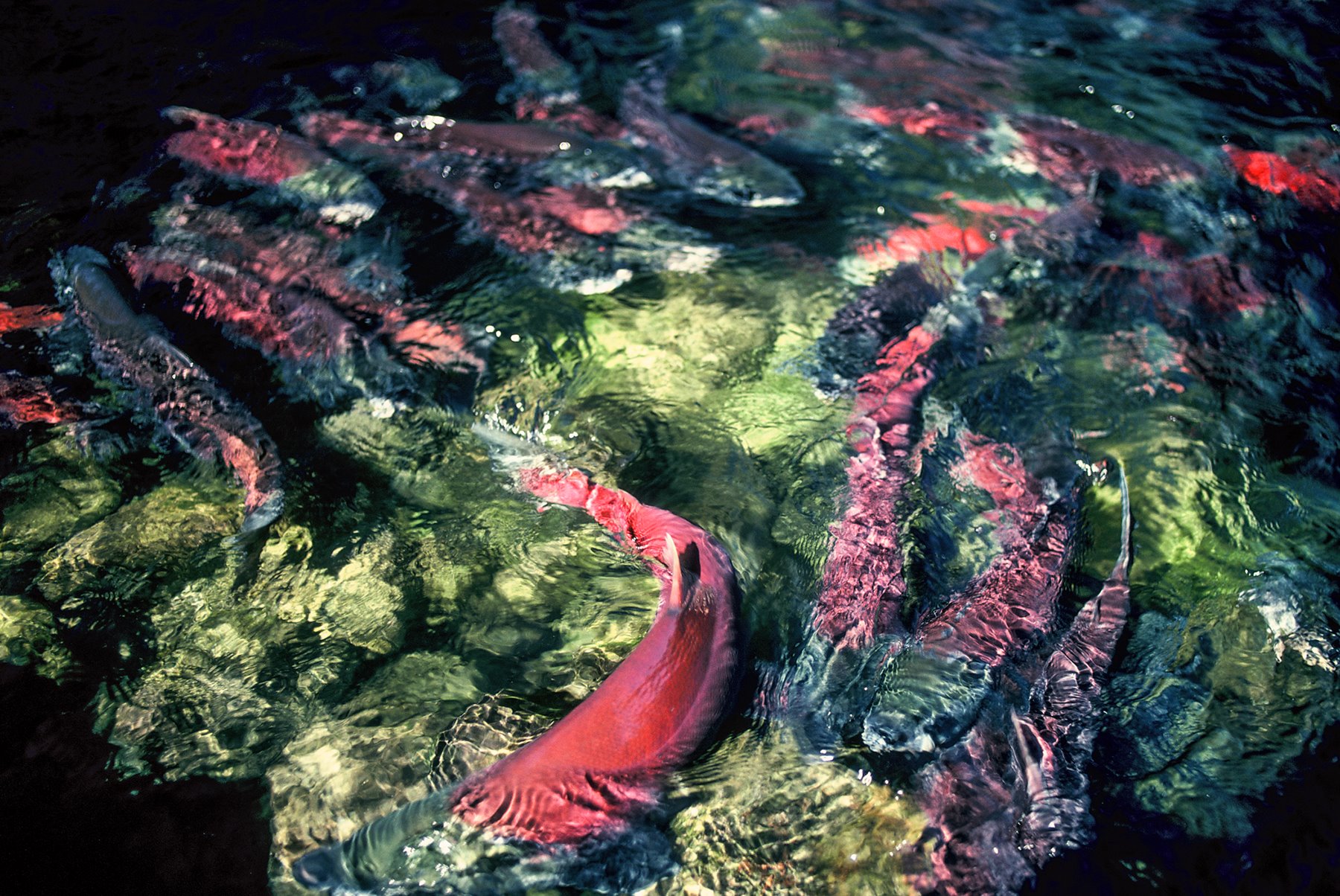

Photo credit: Doane Gregory

The SCC definitively concluded that the trial judge was correct in finding that the Tsilhqot’in had established title to 1,750 square kilometres of land, located approximately 100 kilometres southwest of Williams Lake. The Court reaffirmed and clarified the test it had previously established in Delgamuukw for proof of Aboriginal title, underscoring that the three criteria of occupation: sufficiency, continuity (where present occupation is relied upon), and exclusivity were established by the evidence in this case.

SUFFICIENT AND EXCLUSIVE OCCUPATION

The SCC reasoned that Aboriginal title was not limited to village sites but also extends to lands that are used for hunting, fishing, trapping, foraging and other cultural purposes or practices. Aboriginal title may also extend “beyond physically occupied sites, to surrounding lands over which a Nation has effective control.” The SCC endorsed further examples of Aboriginal occupation sufficient to ground title including “warning off trespassers,” “cutting trees,” “fishing in tracts of water” and “perambulation.”

Further, the SCC affirmed the importance not only of the common law perspective but also of the Aboriginal perspective on title including Aboriginal laws, practices, customs and traditions relating to indigenous land tenure and use. The principle of occupation, reasoned the SCC, “must also reflect the way of life of Aboriginal people, including those who were nomadic or semi-nomadic.”

The SCC reasoned that the criterion of exclusivity may be established by proof of keeping others out, requiring permission for access to the land, the existence of trespass laws, treaties made with other Aboriginal groups, or even a lack of challenges to occupancy showing the Nation’s intention and capacity to control its lands.

WHAT RIGHTS DOES ABORIGINAL TITLE CONFER?

The Court reasoned that Aboriginal title holders have the “right to the benefits associated with the land – to use it, enjoy it and profit from its economic development” such that “the Crown does not retain a beneficial interest in Aboriginal title land.” Expanding on its reasons in Delgamuukw, the SCC concluded Aboriginal title confers possession and ownership rights including:

- the right to decide how the land will be used;

- the right to the economic benefits of the land; and

- the right to pro-actively use and manage the land.

These are “not merely rights of first refusal.” Indeed, the Court recommended that “governments and individuals proposing to use or exploit land, whether before or after a declaration of Aboriginal title, can avoid a charge of infringement or failure to adequately consult by obtaining the consent of the interested Aboriginal group.”

The SCC also reasoned that “the right to control the land conferred by Aboriginal title means that governments and others seeking to use the land must obtain the consent of the Aboriginal title holders.” If consent is not provided, the “government’s only recourse is to establish that the proposed incursion on the land is justified under s. 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982.”

Photo credit: Doane Gregory

JUSTIFICATION ANALYSIS

The Court clarified the justification analysis it set out in Sparrow, Gladstone and Delgamuukw. The Court reasoned that the Crown’s burden of demonstrating a “compelling and substantial” legislative objective must be considered from the Aboriginal perspective as well as from the perspective of the broader public in a manner that furthers the goal of reconciliation between the Crown and Aboriginal Peoples. Further, the Crown must also “go on to show that the proposed incursion on Aboriginal title is consistent with the Crown’s fiduciary duty towards Aboriginal people.” The SCC reasoned that the Crown’s fiduciary duty means that: (1) incursions on Aboriginal title cannot be justified if they would substantially deprive future generations of the benefit of the land; and (2) the fiduciary duty infuses an obligation of proportionality into the justification process that is inherent in the reconciliation process. Implicit in the Crown’s fiduciary duty is the requirement that the infringement be necessary to achieve the government’s goal that the benefits not be outweighed by the adverse effects on the Aboriginal interest, and that the government go no further than necessary to achieve its goal.

The SCC warned that if governments do not meet their obligations to justify infringements to Aboriginal title, and do not act consistent with their fiduciary duties, project approvals may be unraveled, and legislation may fall. The message is that governments that don’t justify their actions act at their peril. The Court offered the following example:

If the Crown begins a project without consent prior to Aboriginal title being established, it may be required to cancel the project upon establishment of the title if continuation of the project would be unjustifiably infringing. Similarly, if legislation was validly enacted before title was established, such legislation may be rendered inapplicable going forward to the extent it unjustifiably infringes Aboriginal title.

IMPACTS OF PROVINCIAL LEGISLATION

In light of its declaration of Aboriginal title, and based on the Forest Act’s definition of “Crown timber” and “Crown lands” not including timber on Aboriginal title lands, the SCC found that the Forest Act did not apply to the Tsilhqot’in’s Aboriginal title lands. The SCC concluded that “the legislature intended the Forest Act to apply to land under claims for Aboriginal title up to the time title is confirmed by agreement or court order.” However, once Aboriginal title is proven, the beneficial interest in the land, including its resources, belongs to the Aboriginal title holder.

On the question of whether provinces can legislate in relation to Aboriginal title and rights, or whether this amounts to an interference with a core area of federal jurisdiction under s. 91(24), the SCC held that the doctrine of inter-jurisdictional immunity did not apply.

The SCC reasoned that the inter-jurisdictional issue in this case was not one of competing provincial and federal powers but, rather, of addressing the tension between the rights of Aboriginal title holders to use their lands as they choose, and the authority of the Province to regulate land use. The SCC concluded that the guarantee of Aboriginal rights in s. 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 operates as a limit on both federal and provincial legislative powers; therefore, the proper way to curtail interferences with Aboriginal rights and to ensure respect from Crown governments, is to require that all infringements, both federal and provincial, are justified.

MOVING FORWARD

This case provides First Nations with significantly improved opportunities to advance their Aboriginal title and rights in a manner that reflects their vision, values and perspectives. The SCC’s decision essentially requires that the Crown and industry meaningfully engage with Aboriginal title holders when proposing to make decisions or conduct business on their territories. This engagement can no longer be limited to “small spots” but must be achieved with a view to tangibly addressing the incidents of title affirmed by this case; namely, the right of enjoyment and occupancy of title land; the right to possess title land; the right to economic benefits of title land; and the right to pro-actively use and manage title land. In this light, as the Court emphasized at para. 97 of its decision, the Crown and industry would be well advised to “avoid a charge of infringement or failure to adequately consult by obtaining the consent of the interested Aboriginal group.”

Pragmatically speaking, this case provides sound guidance for effective and balanced consultation and accommodation discussions regarding decisions taken on Indigenous lands. The principles and laws affirmed in this case, once honoured and implemented, ought to re-invigorate negotiations in relation to the outstanding land question in British Columbia. Opportunities abound.

We acknowledge, with much gratitude and respect the vision, courage and leadership of the Tsilhqot’in people in advancing this case.

This case summary provides our general comments on the case discussed and should not be relied on as legal advice. If you have any questions about this case or any similar issue, please contact any of our lawyers.

See CanLII for the Reasons for Judgement.