On January 13, 2016, the British Columbia Supreme Court (“Court”) released its reasons in the Enbridge Northern Gateway Pipeline (“Project”) case.1 In her decision, Madam Justice Koenigsberg found that a portion of an Equivalency Agreement (“Agreement”)2 entered into between the B.C. Environmental Assessment Office (“EAO”) and the National Energy Board (“NEB”) was invalid to the extent that it abdicated the Province’s decision-making authority by removing the need for the Project to be granted an Environmental Assessment Certificate (“Certificate”). Further, the Court found that the Province had breached the honour of the Crown by failing to consult with the Coastal First Nations (“CFN”) prior to deciding not to terminate the Agreement.

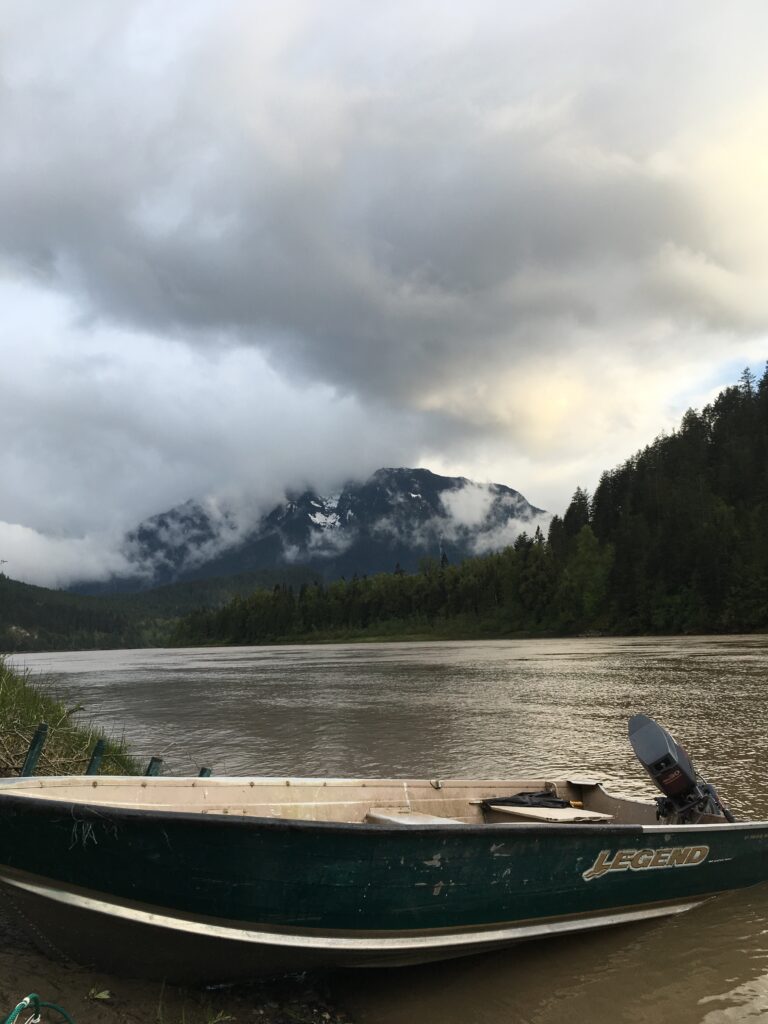

Photo credit: Gordon Lyall

This decision makes it clear that the province cannot abdicate its duty to consult to the federal Crown in respect of projects that require both federal and provincial approval.

I. BACKGROUND

In 2008, and again in 2010, the EAO and the NEB entered into equivalency agreements pursuant to sections 27 and 28 of the B.C.’s Environmental Assessment Act (“EAA”) that purported to remove the need for all reviewable projects requiring both federal and provincial approval to undergo an environmental assessment and to obtain a Certificate from the EAO. In doing so, the EAO purported to abdicate its decision-making authority under EAA as well as its duty to consult and accommodate First Nations. In addition, the Agreement provided the Province with the right to unilaterally terminate the Agreement prior to the federal government’s ultimate approval of a project. CFN was not consulted prior to the Province entering into the Agreement with the NEB.

With the Province ostensibly having abdicated its environmental assessment responsibilities, decision-making powers, and consultation duties as it related to the Project, the NEB and the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency formed a joint review panel (“JRP”) to review the Project. As an intervenor in the JRP review, the Province opposed the Project because it failed to meet five conditions which the Province required to support the Project. In particular, the Province argued before the JRP that it had not been demonstrated that world-class spill response capabilities would be in place for the Project. Despite having the ability to unilaterally terminate the Agreement, the Province chose not to exercise its right. On June 17, 2014 the federal government approved the Project with four out of the five conditions set by the Province unmet.

CFN3 sought judicial review of the EAO’s decision to enter into the Agreement arguing that while the EAA granted the EAO jurisdiction to accept another jurisdiction’s assessment of the project, the EAA did not authorize the EAO to abdicate its decision-making authority to grant a Certificate under the Act. In addition, CFN argued that they were owed a duty to consult prior to the Province entering into the Agreement and before the Province decided not to terminate the Agreement.

Photo credit: Gordon Lyall

II. THE DECISION

1) Statutory Interpretation

The Court began by addressing Northern Gateway Pipelines Inc.’s argument that B.C.’s decision-making powers under EAA could not apply to the Project because the Project is within the exclusive jurisdiction of the federal government. The Court disagreed noting that while the Province could not outright refuse to issue a Certificate for the Project, it could issue further conditions in addition to those imposed by the federal government.

The Court then turned to the interpretation of the EAA. The Court noted that both the Province and CFN agreed that the Northern Gateway Pipeline was a reviewable project pursuant to the EAA. A reviewable project must undergo an environmental assessment and then obtain a Certificate, unless the Minister (in his discretion) determines that the project would not have significant adverse environmental, economic, social, heritage or health effects and exempts it from this process. As the Minister did not exercise his discretion in this instance, a Certificate was required.

While the Court acknowledged that the EAA grants the Province broad discretion to enter agreements that relate to any aspect of environmental assessment, the Court concluded that British Columbia’s unique objectives, political and social goals, and legal obligations that led to the enactment of the EAA required an interpretation of the EAA that did not allow the Province to abdicate its decision-making authority (i.e. the need to make a determination as to whether or not a project should be granted a Certificate):

…it cannot be the intention of the legislators to allow the voice of British Columbia to be removed in this process for an unknown number of projects, when the purpose behind the EAA is to promote economic interest in this province, and to protect its land and environment.

For these reasons, the Court held that the Agreement was invalid to the extent that it purported to remove the need for reviewable projects to obtain a Certificate under the Act.

2) The Duty to Consult and Accommodate

The Court went on to consider whether the Province had a duty to consult with the CFN in respect of the Project. The Court rejected the Province’s argument that the Agreement shifted sole responsibility for the duty to consult and accommodate to Canada, noting that both the federal and provincial Crown owe “specific responsibilities to consult First Nations as their respective legislative powers intersect and affect s. 35 guarantees.” However, the Court held that the province owed CFN no duty to consult prior to entering into the Agreement because there was little possibility that CFN’s Aboriginal rights would be adversely impacted by the Agreement and the Province retained the ability to unilaterally terminate the Agreement. Nonetheless, the Province owed CFN a duty to consult and accommodate on the Project and the duty needed to be met before the Province decided not to terminate the Agreement.

The Province admitted that it did not engage CFN in any consultation prior to deciding not to terminate the Agreement despite having knowledge of CFN’s concerns; concerns that largely coincided with those expressed by the Province to the JRP. The Province argued that consultation mattered little given the extensive work it had completed in developing a world-leading spill response for the Province. The Court rightfully noted the “paternalistic and now discredited nature” of the Province’s argument – stating that the Province’s approach to dealing with the issue looked very much like “we know best and have your best interests at heart”. Significantly, the Court stated that for consultation to be meaningful, early and meaningful dialogue is required and affected First Nations must “be consulted as policy choices are developed on how to deal with potential adverse effects of government action or inaction.” [emphasis added]

Finally, the Court noted that the Province’s ability to give effect to its obligation to consult and accommodate with CFN was significantly impaired by the Province failing to terminate the Agreement. Any opportunity to attach conditions to the Project’s approval was lost when the Agreement was not terminated before the Project was approved, limiting the Province’s ability to do much more than ask the federal government to accommodate both the Province’s and CFN’s concerns.

III. THE REMEDY

The Court held that the Agreement was invalid to the extent that it purported to remove the need for a Certificate, and declared that the Province is required to make a decision on whether or not to grant the Project a Certificate. In addition, Justice Koenigsberg declared that the Province owes a duty to consult First Nations which is triggered by the Province making a decision as to whether the Agreement should or should not be terminated. Similarly, the Province was required to consult with First Nations about potential impacts of the Project on areas of Provincial jurisdiction and how to address those impacts in a manner consistent with reconciliation and the honour of the Crown.

IV. POTENTIAL IMPLICATIONS

1) Northern Gateway

This decision does not reset the Project’s approval process; the Court was clear that the Province may rightfully adopt the NEB’s assessment of the Project – it needn’t engage in its own environmental assessment of the Project. However, the Province must now consult about the impacts of the Project and how to address those impacts, and then come to a decision as to whether or not the Project should be issued a Certificate. In the words of Justice Koenigsberg:

the Province is free to issue an EAC with no conditions for this Project, or it can impose conditions that can be reviewed later should any party to these proceedings take issue with any that are imposed. Total discretion in this regard rests with the Province.

2) Trans Mountain and other projects

The Agreement is not project specific. It applies to all reviewable projects that require both federal and provincial approval. As the Northern Gateway Pipeline Process and the Trans Mountain Process are subject to the same equivalency agreement, British Columbia will likely be required to consult on impacts of the Trans Mountain Pipeline on First Nations in areas of provincial jurisdiction before the Trans Mountain Pipeline can be approved. In addition, the Province must likely come to a determination as to whether or not the Trans Mountain Pipeline should be issued a Certificate and may or may not attach its own conditions to pipeline approval.

3) Duty to Consult about Policy Choices

Interestingly, the Court stated that:

Consultation, to be meaningful, requires that affected First Nations be consulted as policy choices are developed on how to deal with potential adverse effects of government action or inaction. Hobson’s choices are no longer sufficient. [para. 209, emphasis added]

This is further recognition of the need for the Crown to engage with First Nations at the policy level in order to ensure that the duty to consult is met.

This case summary provides our general comments on the case discussed and should not be relied on as legal advice. If you have any questions about this case or any similar issue, please contact any of our lawyers.

See CanLII for the Reasons for Judgement.

Footnotes

1 The Northern Gateway Pipeline would stretch from Bruderheim, Alberta to Kitimat, British Columbia and would mostly carry diluted bitumen from the Alberta oil sands to a marine terminal at Kitimat. The BC portion of the pipeline would cover approximately 660 kilometres and cross some 850 watercourses. Tankers would carry the diluted bitumen through BC coastal waters to world markets. The vast majority of land and waters utilized to transport the diluted bitumen are currently and traditionally used by Indigenous groups.

2

3 CFN is a provincial incorporated society whose member First Nations include the Wuikinuxv Nation, Heiltsuk, Kitasoo/Xaixais, Nuxalk Nation, Gitga’at, Metlakatla, Old Massett, Skidegate, and Council of the Haida Nation.