13. The charge of the Indians, and the trusteeship and management of the lands reserved for their use and benefit, shall be assumed by the Dominion Government, and a policy as liberal as that hitherto pursued by the British Columbia Government shall be continued by the Dominion Government after the Union.

To carry out such policy, tracts of land of such extent as it has hitherto been the practice of the British Columbia Government to appropriate for that purpose, shall from time to time be conveyed by the Local Government to the Dominion Government in trust for the use and benefit of the Indians on application of the Dominion Government; and in case of disagreement between the two Governments respecting the quantity of such tracts of land to be so granted, the matter shall be referred for the decision of the Secretary of State for the Colonies.

Though the “official” date of BC’s entrance into Confederation is July 20, 1871, today—May 16—marks the anniversary of Britain’s acceptance of the Terms of Union.

Most British Columbians complete their education with only a vague sense of how their province became a part of Canada. Some might remember something about the Colony being enticed by promises of a railway connecting the west coast with the eastern Canadian provinces. Few likely remember learning of the years of negotiations between imperial, federal, and colonial representatives who settled the terms by which the Colony became the Province of British Columbia.

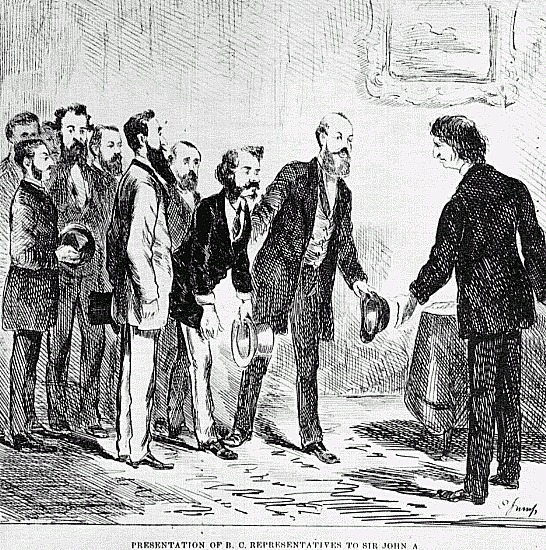

BC Delegation to Ottawa. Canadian Illustrated News, May 11, 1872.

The clause that most affects Indigenous people in BC today is Article 13, which divided responsibilities for Indigenous people between the two governments. The Terms assigned to Canada “charge of the Indians, and the trusteeship and management of the lands reserved for their use and benefit,” which echoed the British North America Act’s section 91(24). BC bore the responsibility of conveying lands to Canada “in trust for the use and benefit of the Indians on application of the Dominion Government.”

These divided responsibilities caused decades of legal and political wrangling that has yet to be put to rest. Both governments agreed that, as a pre-existing colony, the new province entered Confederation with exclusive control of its public lands. Canada knew that the colonial government had allotted some Indian reserves in the Colony and so acceded to Article 13’s stipulation to uphold “a policy as liberal as that hitherto pursued by the British Columbia Government.” On the recommendation of the first federal Superintendent of Indian Affairs in BC, Canada attempted to establish a standard of 80 acres of reserve land for every Indigenous family.

The Province, however, thought that standard excessive and rejected it outright. Both the Colony—and subsequently the Province—held a parsimonious definition of “liberal” since the Indian reserve policy west of the Rockies catered to the desires of incoming settlers over the rights of First Nations. In the years before Confederation, many settlers in the Colony commented sarcastically that they “were not aware that our Government had an Indian policy” but only because they believed that “the ridiculously large and promiscuous so-called Indian Reserves have been a chronic subject of complaint, and have in several parts of the Colony seriously retarded settlement.”

Where Canadian officials emphasised Article 13’s “liberal,” the provincial government made hay from the Terms of Union’s “as…hitherto pursued.” Though the Colony had no legislated Indian reserve policy, its general practice had been to allot reserves at a scale of roughly ten acres for a family of five and to ensure that these allotments did not interfere with lands claimed by settlers. It had also prohibited Indigenous people from pre-empting land (though purchases were theoretically possible) and denied the existence of any underlying Aboriginal title to the land.

The conflicting vision of a “liberal” Indian reserve policy led to the creation of the Joint Indian Reserve Commission in 1876, and the Indian Reserve Commission in 1878, which were intended to achieve a “speedy and final adjustment of the Indian Reserve question” in the Province by sending jointly-appointed commissioners to local Indigenous communities to settle disputes with settlers and provide for each community’s needs.

The results were neither speedy nor final. In 1907, after many acrimonious years, BC refused federal requests for further Indian reserves until Canada acknowledged that the Province held the underlying title to the reserves. The two governments eventually accepted many of the reserve confirmations, allotments, reductions, and cut-offs recommended by a Royal Commission that operated from 1912 to 1916, but they only did so eight years later after a subsequent joint review of the Commission’s final report. The joint reviewers stated that their revised version of the Royal Commission’s decisions constituted a “full and final adjustment and settlement” of disagreements between the two governments “in fulfillment of…Section 13 of the Terms of Union” except in areas covered by Treaty 8.

Many Indigenous-led organizations rejected the Commission’s final report altogether because it did not consider related and essential issues like fishing, hunting, and water rights, the Province’s continued claims to a reversionary interest in reserve lands, and the question of Aboriginal title. The Allied Indian Tribes, in a 1919 statement issued in response to the Commission’s report, included reference to the Terms of Union in two of its nine grounds for rejecting the Commission’s report:

3. The whole work of the Royal Commission has been based upon the assumption that Article 13 of the Terms of Union contains all obligations of the two governments towards the Indian Tribes of British Columbia, which assumption we cannot admit to be correct.

4. The McKenna-McBride Agreement, and the report of the Royal Commission ignore not only our land rights, but also the power conferred by Article 13 upon the Secretary of State for the Colonies.

Beyond nineteenth century Indian reserve policy and early-twentieth century Royal Commissions, many of today’s most important judicial decisions hinge on interpretations of the Terms of Union’s Article 13, especially with regard to Canada’s fiduciary duty to Indigenous people in the Province (see 2014 SCTC 3, 2018 SCC 4, 2020 SCTC 1, 2019 SCTC 2, 2013 SCTC 1, 2016 SCTC 3).

Even if the ratification of the Terms of Union is not an event to celebrate, it is certainly a date worth commemorating.